Translation doesn't entirely work and maybe that's the point

Not-knowing as a spiritual practice

Dear friend,

This past little while I’ve been working on a book of winter folklore with the publisher Hyldyr, which (gods willing) will be available this December. The book will include pieces from the many medieval and folkloric sources I’ve gathered over my years of researching and teaching about folklore and paganism.

As I’ve been putting the pieces together for this project, a certain desire has been tugging at my being: I have really wanted to include some riddles. I’m sure I’m not alone in this, but I passionately desire to be a part of a riddle revival. Can we bring back the riddle, please?

I’ll go first.

I was at a family gathering two weeks ago, and a few of us were sitting around a table, brainstorming conversation topics. It was a literary, whimsical sort of group, so I asked if anyone knew any riddles by heart. Not off the top of their heads, they said. I could think of just one:

A little fat man in a bright red coat

a staff in his hand and a stone in his throat.

They received my riddle graciously and gave it plenty of time and guesses. I loved the old-fashioned experience of waiting and thinking together as a group, without recourse to the internet, which would have given us the answer immediately. They eventually solved it organically, which means —as my nerdy heart desires— they might even remember it and tell it to someone else one day. The answer, if you want it, will be at the bottom of the post.

There is something extremely generative in the minutes, even hours, years, possibly, between the moment when you encounter some bit of communication, written or spoken, and the moment when you finally understand it to your satisfaction. I imagine that in the golden days of oral tradition, chewing on a riddle was something like waiting for a good piece of mail. The possibilities of what it might yield are, for the moment, infinite. While you wait you are busy imagining. You are busy building possible worlds.

I’m old enough to remember waiting for physical mail: the Sears “Wishbook” Christmas catalogue (from which my family never ordered a thing but which gave me many dreams); or a letter from my earnest penpals in Ghana and Malaysia. Even as an adult living in northern Canada I’ve been accustomed to waiting five weeks for a package containing a book of folklore or a sweater.

What comes in the mail is always different than what we envisioned, and that is also part of the pleasure. The time between the missive and its arrival, the walking to the post office or box every day in anticipation, holds an embodied quality of potentiality that is irreduceable to whatever is actually making its merry way to your door.

Can you call to mind the feeling that inhabits your body when you are waiting for something good to happen? Maybe you have tickets to see your favourite band in a couple of weeks. Maybe you bought a flight somewhere amazing. How does that feel? And how do you relate to the world in the meantime? I’ve noticed that when I’m expecting something good to happen, more good things, unrelated to the original notion, tend to happen. I smile at the person who made my coffee. I make jokes with little old ladies on the street. The sun shines brighter. Even gettting caught in the rain on my bicycle can be invigorating.

Because something good is surely on its way.

After my recent fruitful encounter with the practice of riddle-sharing, I resolved to learn more of them. And as I dove into this current winter folklore project I came across a resource I’m amazed I hadn’t encountered before. It’s called the Exeter Book. It is a 10th century manuscript containing the largest collection of Old English poetry in existence, including around ninety-five riddles. Ninety-five Old English riddles! Is this not the treasure-trove of the ages? I had heard the name “Exeter book” before, but I didn’t realize what it meant. It’s pure gold. Tolkein obviously slept with an edition on his bedside table. One day maybe I will, too.

And.

Would you believe that the writer of the riddles in the Exeter book didn’t include any of the solutions to the ninety-five-or-so riddles? What an absolute jape! This fact tortures and intrigues me in equal measure. As a result of the Exeter scribe’s cheeky omission, there are riddles pitched one thousand f***ing years ago that have yet to be satisfyingly unriddled. The wonder of it!

Here’s one of the unsolved ones:

I am noble and known to men of rank, and I rest often; to rich and poor, to people far and wide I am known, and to me, formerly estranged from friends, remains the hope of plunderers, if I should have honour in the cities or bright wealth.

Now wise men above all cherish my company; to many I must tell of wisdom, where they speak not a word, nothing throughout the earth. Though now the sons of men, sons of land-dwellers, eagerly seek my tracks, I sometimes hide my trail from all of them.

Of course there are many theories for the solutions to these “unsolved” riddles, and it’s likely that for some multiple solutions exist. In fact, the cleverness of several Exeter riddles derives from a sort of bait-and switch where the reader is invited to imagine a crudely erotic message, when a more prosaic, commonplace one is subtly implied, such as in this one here (hold onto your hats, it’s racy).

Part of the diffuculty in interpreting Old English riddles derives from the fact they’re written in a different language than we speak. And many of the Exeter riddles refer to everyday objects, many of which would be unrecognizable to us now. The riddle’s invitation has been despatched, and over the centuries it was lost in the mail, the mystery calling out into eternity, ever inviting us to unravel it. How painful this is for the curious mind!

But what if the invitation is enough? Isn’t it incredible we can still hear the voice of the dead, even if it speaks in another tongue entirely? Is it possible that sometimes the longing for understanding is more compelling than the understanding itself?

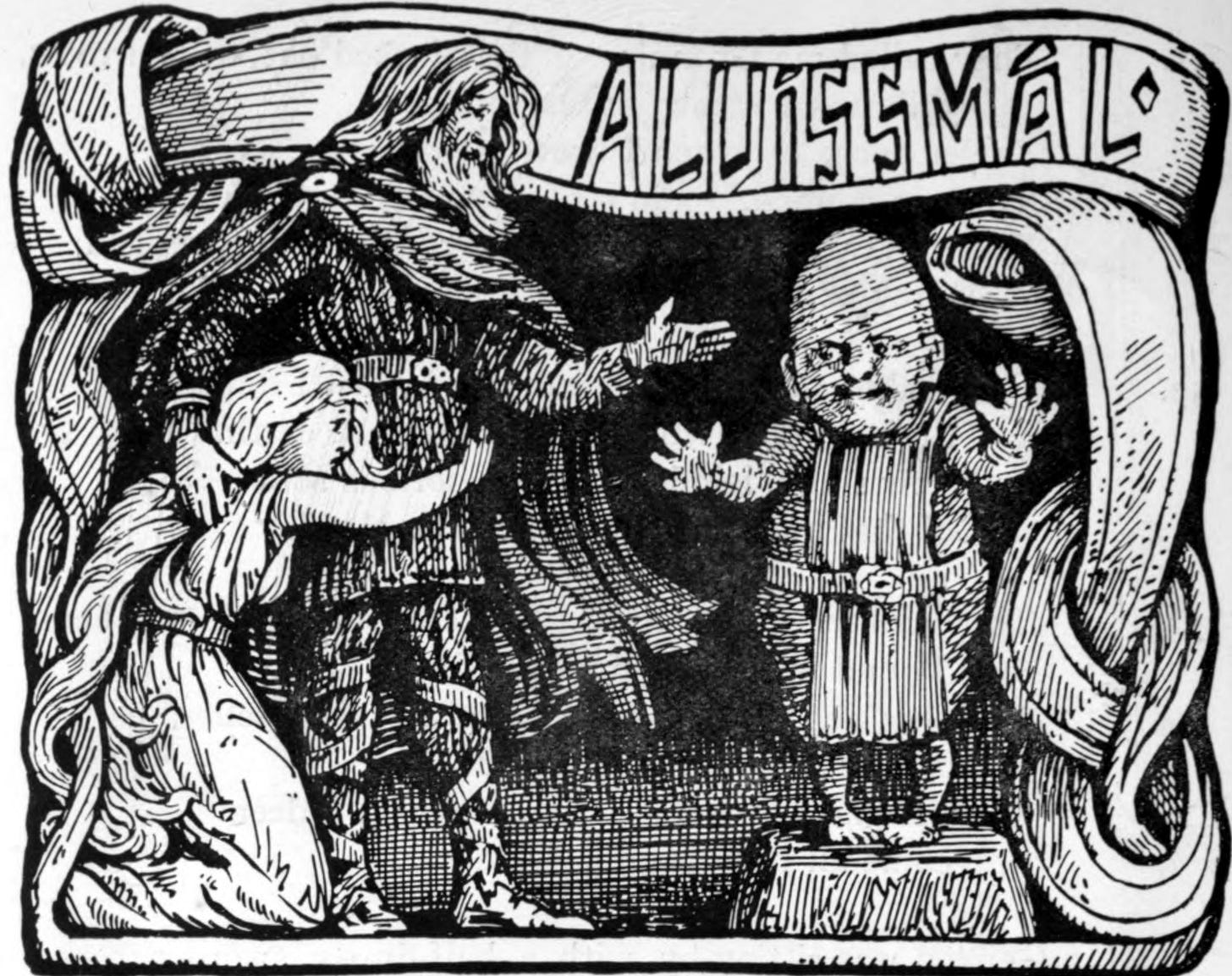

An entry on riddles in the Handbook of Medieval Folklore reminded me that there are riddle-like stanzas in the Old Norse poem Alvíssmál of the poetic Edda (one of the main sources for what we call Norse Mythology), which stages a battle of wits between Thor an a dwarf named Alvís, All-Wise.

And let me say, this is a trippy poem. I remember when I first read it, a couple of years ago, I was absolutely delighted. It’s full of pagan cosmology and delicious metaphor. And its characterization of Thor suprised me. We are accustomed to seeing the thunder god as good-hearted but rather blunt instrument, facing off against jötnar or getting into goofy escapades, defending his (fragile?) masculinity with violence. Here we see him firmly in the wisdom literature genre, engaged in learned banter with a dwarf about the nature of the universe, a situation in which we would better expect to see Odin, or even Loki.1 And the riddling is strong.

What’s especially compelling about Alvíssmál, and what inspired me to write this post today, is the fact that the poem foregrounds the idea that multiple possible translations for natural phenomena are possible. It invites us to imagine the sky, the sun, the moon, the wind, the forest, and more, from the various perspectives of different mythic races in Old Norse cosmology, as he puts it “in each and every world.”

I’ll share a few lines here:

“Thor spake:

"Answer me, Alvis! | thou knowest all,

Dwarf, of the doom of men:

What call they the wood, | that grows for mankind,

In each and every world?"

Alvis spake:

"Men call it 'The Wood, | gods 'The Mane of the Field, 'Seaweed of Hills' in hell;

'Flame-Food' the giants, | 'Fair-Limbed' the elves,

'The Wand' is it called by the Wanes."

Thor spake:

"Answer me, Alvis! | thou knowest all,

Dwarf, of the doom of men:

What call they the night, | the daughter of Nor,

In each and every world?"

Alvis spake:

"'Night' men call it, | 'Darkness' gods name it,

'The Hood' the holy ones high;

The giants 'The Lightless,' | the elves 'Sleep's joy"

The dwarfs 'The Weaver of Dreams."'

Thor spake:

"Answer me, Alvis! | thou knowest all,

Dwarf, of the doom of men:

What call they the seed, | that is sown by men,

In each and every world?"

Alvis spake:

"Men call it 'Grain,' | and 'Corn' the gods,

'Growth' in the world of the Wanes;

'The Eaten' by giants, | 'Drink-Stuff' by elves,

In hell 'The Slender Stem.”

Isn’t it beautiful? One of the most enjoyable things (for me) about reading texts translated from Old Norse is the fact they come with copious footnotes, so I know that the translator made difficult choices about the words they would choose, and that others came before and came to different conclusions.

Even as we try to know the past, even as we try to become wise, the magic of the world remains to a degree unknowable. How often can we take that unknowability as an invitation to collaborate? What if all is not (yet) known? Isn’t that the most liberating notion of all?

There’s more medicine in the conclusion to this contest between Thor and All-Wise. Though the dwarf knows all of the names for all of the things in all of the worlds, he fails to notice one important detail about the real-time exchange he is having with Thor. While he has been distracted by delivering his perfect recitation, the sun has been rising and angling its way through a chink into the hall where the two of them stand. All-Wise, ironically, didn’t have his wits about him, and the rising sun turns him to stone.

It seems to me this poem offers a gentle corrective to the temptation to lean into certainty, especially in our engagement with tradition as it’s handed to us, assuming its wisdom is fully knowable, or complete. As we long for the inheritance of an unbroken lineage, for the native wisdom that was erased in the Roman and Christian expansions across Europe, it’s easy to forget that this ancient poetry, along with (basically) all literature for most of our ancestors, existed entirely in the oral tradition.

This mythic poetry was alive. The teller of the poem owned it as well as anyone else and could do what they liked with it. A myth might feature a different god when a different person told it. A riddle might have a different solution. What makes something alive? It grows and it changes.

Isn’t that a little frightening?

[What about all the sacred knowledge that got lost?]

And isn’t it exciting?

[What about all of the sacred knowledge that’s still to come?]

There is something about the translation of poetry (and mistranslation, even) that gives me a sort of unnacountable thrill. I like the fact that when I read Robert Bly’s translation of Rilke’s poem Moving Forward Bly has him “standing on fishes” even though in English that might not make sense. Maybe it didn’t even make sense in the original German.

In any case, I remember reading that translation for the first time as an undergrad and feeling exactly like that. Like I was standing on fishes. The ground was moving; the ground was shimmering. I couldn’t be sure what was “intended” by Rilke, the original author. But something was emerging from the chasm in between his words and my mind that felt uncanny, freeing, even slightly irresponsible. I was an English student. I was supposed to try my damndest to Understand the Meaning of The Author. And in this moment, I couldn’t. And I loved it.

The definition of a riddle is a description of an object or an idea with a key piece of information missing. Therein lies the thrill. There is a wild sort of agency in the gap between what’s offered and what’s received.

What mystery are you sitting with today, friend? What piece of understanding is evading you? And might there be some pleasure in the imaginative world that grows in the green and rushing chasm in between?

Love,

Danica

PS: herein lies the answer to the first riddle.

Scroll down for the paid-subscriber audio!

Thank you to all the folks who have signed up for this workshop!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Danica Boyce at Enthusiastica to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.